Working in the Negative Space of Content and Analysis

One of the most influential books I’ve read on creativity is Steal Like an Artist. I picked it up because of the title. What made it stick was how it described a process that applies well beyond art—especially in an environment where content volume has outpaced understanding.

First published in 2012, the book is not about copying. It is about content synthesis. Kleon’s argument is straightforward: ideas are developed by studying existing work, understanding its structure and limits, and contributing something that was not previously articulated.

That framework maps cleanly to how I approach SEO and content strategy.

You examine what ranks, how topics are consistently framed, and where multiple sources repeat the same information with minor variation. The task is not to replicate what already performs. It is to identify where coverage breaks down or stops short. In practical terms, that is gap analysis.

What is gap analysis really describing? It is the process of identifying where information is missing, outdated, or incomplete. When applied specifically to content, content gap analysis becomes a diagnostic exercise. You are not looking for keywords alone. You are identifying unresolved questions, weak explanations, and gaps in the existing material where related facts fail to connect.

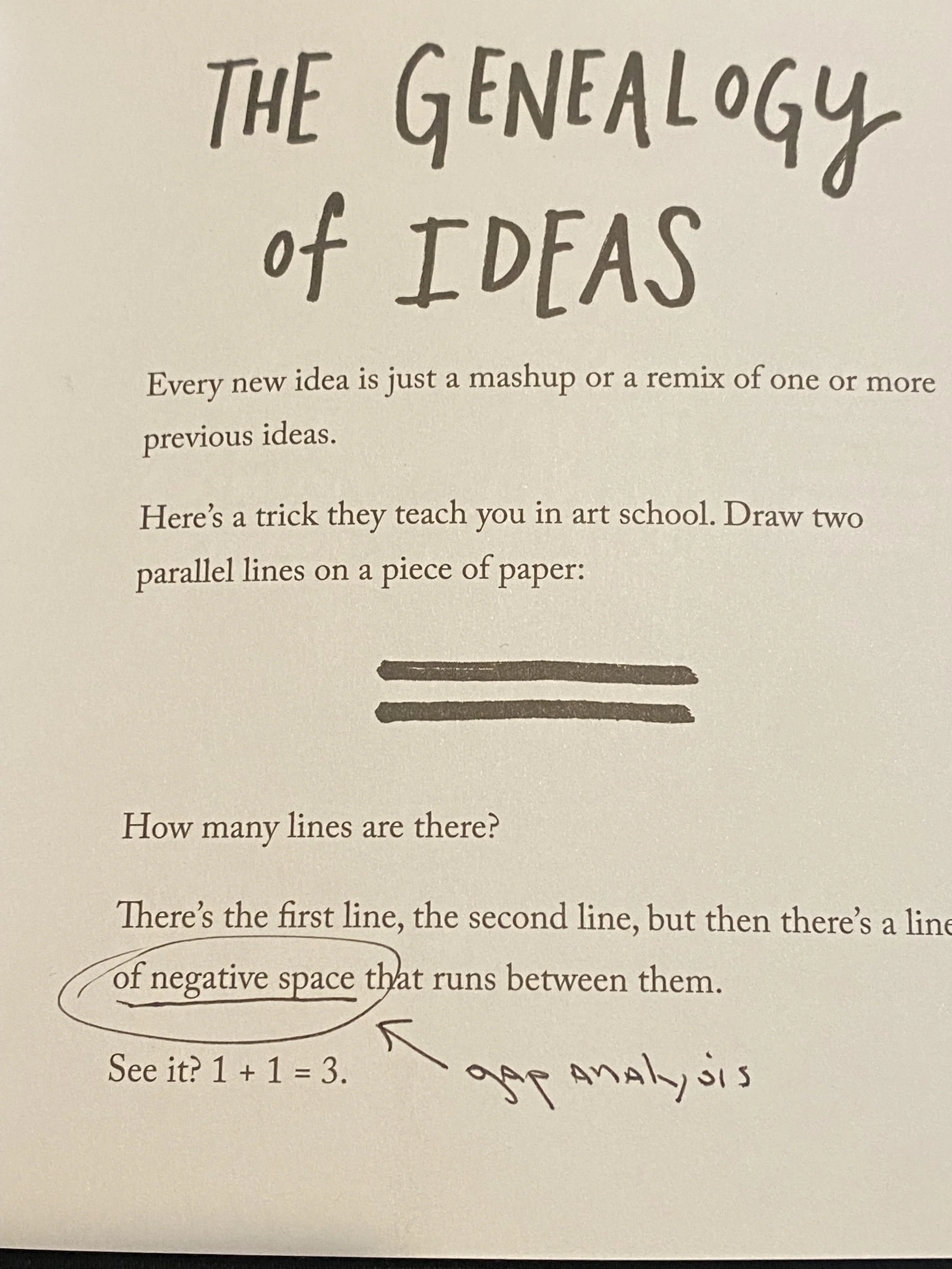

Kleon illustrates this idea with a simple example:

Draw two parallel lines on a page. At first glance, there are two lines. Look more closely, and a third appears; the space between them. That space is not empty. It defines the relationship between the two visible elements.

Most content focuses on the visible lines: the topics already being addressed.

Content gap analysis trains you to focus on the space between them. That space might be an assumption that goes unchallenged, an operational detail no one explains, or a failure to reconcile overlapping information from different sources. That is where new value is created.

This is the same approach I use whether I’m building search-driven editorial content or synthesizing multiple sources of content. The objective is to understand what exists, identify what does not, and work deliberately in that space.

For anyone working in content creation, analysis, or research-driven fields, this book is worth reading. It reinforces a discipline that’s increasingly rare: creating by understanding first.