The Modern Identity Footprint: Signals, Documents, and Information Exhaust

Personal security is no longer defined solely by passwords, locks, or encryption. Identity exposure today is built across paper records, electronic signals, transaction metadata, and device behavior. Each individual leak may appear insignificant. Over time, those fragments form a usable profile.

Most public discussion treats privacy threats as discrete problems: cybercrime, RFID skimming, phone tracking, or identity theft. What is rarely addressed is how these threats overlap and reinforce one another. The risk is not any single vulnerability, but the accumulation of small, persistent breaches that are easy to collect and difficult to erase.

Viewed together, modern personal protection is about controlling information exhaust rather than eliminating risk outright.

The Scope of the Threat Environment

Cybercrime has shifted from opportunistic exploitation to an industrial scale. Estimates projecting trillions in annual global losses matter less for their precision than for what they indicate: data exploitation is now routine, automated, and persistent.

At the same time, everyday technologies normalize constant signal emission. Contactless payments, RFID-enabled IDs, background app telemetry, cloud storage, and location-aware devices generate data even when users are not actively engaging with them. Participation in modern life produces traceable output by default.

Identity compromise rarely begins with a single breach. It is usually assembled incrementally:

• Discarded mail containing partial identifiers

• Receipts that reveal location and purchasing behavior

• RFID-enabled cards confirming physical presence

• Mobile devices broadcasting location, network, and device metadata

• Cloud-accessible documents tied to compromised endpoints

Paper Trails and Physical Identity Leakage

Despite the focus on digital threats, a significant portion of sensitive personal data still exists in physical form. Mailboxes, trash cans, and recycling bins remain high-yield collection points for identity thieves.

Personally Identifiable Information (PII) is broader than many people assume. It includes not only obvious identifiers such as Social Security numbers, but combinations of ordinary documents:

• Full name

• Financial statements or account numbers

• Medical or legal paperwork

• Store receipts

• Email addresses

• Signatures

• Passport or driver’s license numbers

Individually, these items may appear harmless. Collected over time, they reveal patterns in employment, family structure, financial behavior, and daily routines.

Within military and intelligence communities, this process is known as building a target package: gathering fragments, validating them through overlap, and using the resulting profile operationally. Identity theft follows the same logic, even if the terminology is different.

Document Destruction as Risk Reduction

Disposal is where most people fail—not from negligence, but from misunderstanding how reconstruction works.

Tearing documents by hand or using basic strip-cut shredders does not meaningfully deny access. Reconstruction is straightforward with time, patience, and modern tools. Effective destruction depends on fragment size, distribution, and final disposition.

Shredding Security Levels Explained

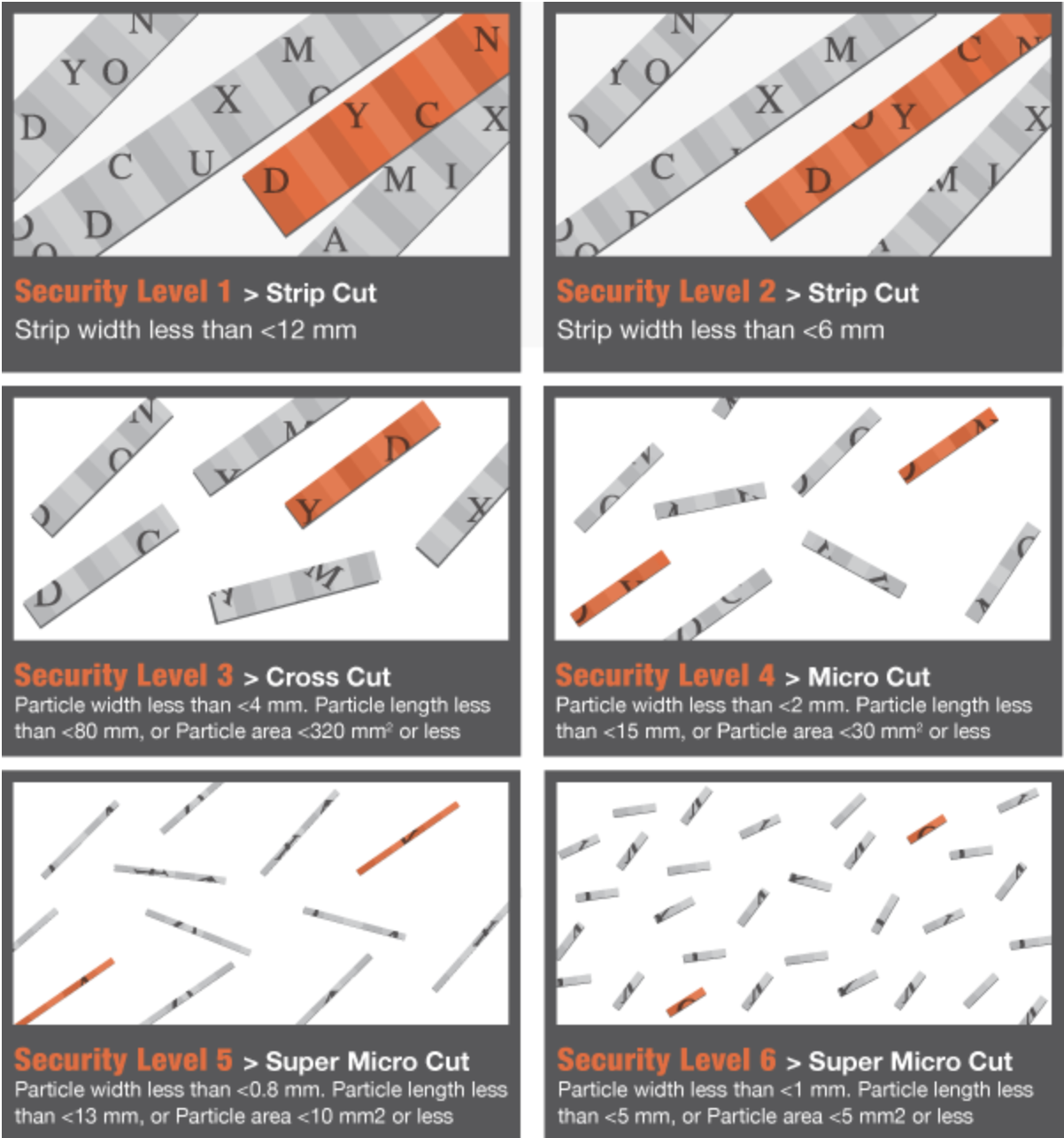

Paper shredders are classified by security levels that define how small documents are reduced:

• P1–P2: Strip-cut or large cross-cut. Intended for low-risk internal documents. Easily reconstructed.

• P3: Cross-cut shredding suitable for sensitive personal information. Acceptable baseline for PII.

• P4: Finer cross-cut significantly increases reconstruction difficulty.

• P5: Designed for highly sensitive material. Reconstruction becomes impractical.

• P6: Extremely fine shredding used for classified material. Approved for top-secret handling in government contexts.

For civilian use, P3 or higher is the practical minimum. Strip-cut shredders should be avoided entirely. They produce long, readable fragments that offer only the illusion of security.

Why Shredding Alone Is Not Enough

Even properly shredded documents remain readable in fragments until they are destroyed completely. Shredded material stored in household trash or recycling bins still represents recoverable data.

This is why government and military organizations pair shredding with incineration. Shred first to allow airflow and consistent burn, then destroy the fragments entirely.

Burn bags, whether official government versions or clearly marked containers, serve a practical purpose. They prevent shredded material from being mistaken for ordinary waste and reintroduced into the collection stream.

Signal Emissions and the Myth of “Offline”

Electronic devices rarely become inert simply because they are powered down or placed in airplane mode. Modern smartphones contain multiple radios, background processes, and non-removable batteries. Many continue emitting identifiable signals unless physically isolated.

This reality is well understood in intelligence and national security circles because it underpins SIGINT—signals intelligence.

SIGINT and Data “Pulled Out of the Air”

Signals intelligence refers to the collection and analysis of electronic signals as they move through the electromagnetic spectrum. This includes cellular transmissions, Wi-Fi traffic, Bluetooth handshakes, GPS signals, and other radio-frequency emissions.

From an intelligence perspective, the data does not need to be “sent” deliberately to be collected. Devices constantly announce themselves seeking networks, authenticating connections, synchronizing time, or exchanging metadata. These emissions can be intercepted, logged, and correlated.

SIGINT is not limited to message content. In many cases, metadata is more valuable than payloads:

Device identifiers

Network associations

Location data

Timing patterns

Frequency usage

Even encrypted traffic reveals information simply by existing. The presence of a signal confirms the presence of a device, a location, and a behavior pattern. This is why intelligence agencies describe data collection as pulling information “out of the air” rather than hacking devices directly.

For civilians, this distinction matters. The threat is not limited to malicious actors actively attacking a device. Passive collection alone can establish patterns and associations over time.

Why “Off” Is Not Off

Turning a phone off or enabling airplane mode does not guarantee silence. Many devices retain active radios or resume transmission automatically. Most modern phones do not allow battery removal, eliminating the simplest form of physical shutdown.

From a SIGINT perspective, this means a device that exists can often be detected, even if it is not being actively used.

This is why software-based controls are insufficient for certain use cases. Encryption protects data in transit, not the fact that transmission exists.

Smartwatches as Signal Multipliers

Smartwatches are often overlooked in discussions about electronic exposure because they are framed as accessories rather than devices. From a signals and counterintelligence perspective, that framing is incorrect. A smartwatch is not an extension of a phone; it’s an additional node.

Unlike phones, smartwatches are designed to be always on, always worn, and always collecting. They broadcast Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and, in many cases, cellular signals. They log location, movement, sleep patterns, heart rate, and daily routines. That data is stored locally, transmitted to paired devices, uploaded to cloud platforms, and frequently shared with third-party applications.

This constant collection creates value for consumers. It also creates risk.

Intelligence and counterintelligence professionals have long recognized wearables as a liability in environments where anonymity or discretion matters. Former CIA officers have publicly stated that smartwatches are inappropriate for human intelligence operations precisely because they undermine one of the core requirements of clandestine work: remaining “black,” or free from hostile surveillance. The issue is not that the devices are malicious. It is that they generate a persistent, detailed record of behavior that can be collected, analyzed, and correlated after the fact.

Pattern of Life and Passive Collection

Smartwatches are uniquely effective tools for pattern-of-life analysis. They do not simply show where someone was at a single moment. They reveal routines over time: when someone wakes up, where they exercise, how often they visit specific locations, how long they remain there, and how their behavior changes.

The risks of this kind of data exposure are not theoretical. Fitness tracker data has repeatedly been used to reveal sensitive military installations, government facilities, and protective security patterns. In some cases, it has contributed directly to real-world violence.

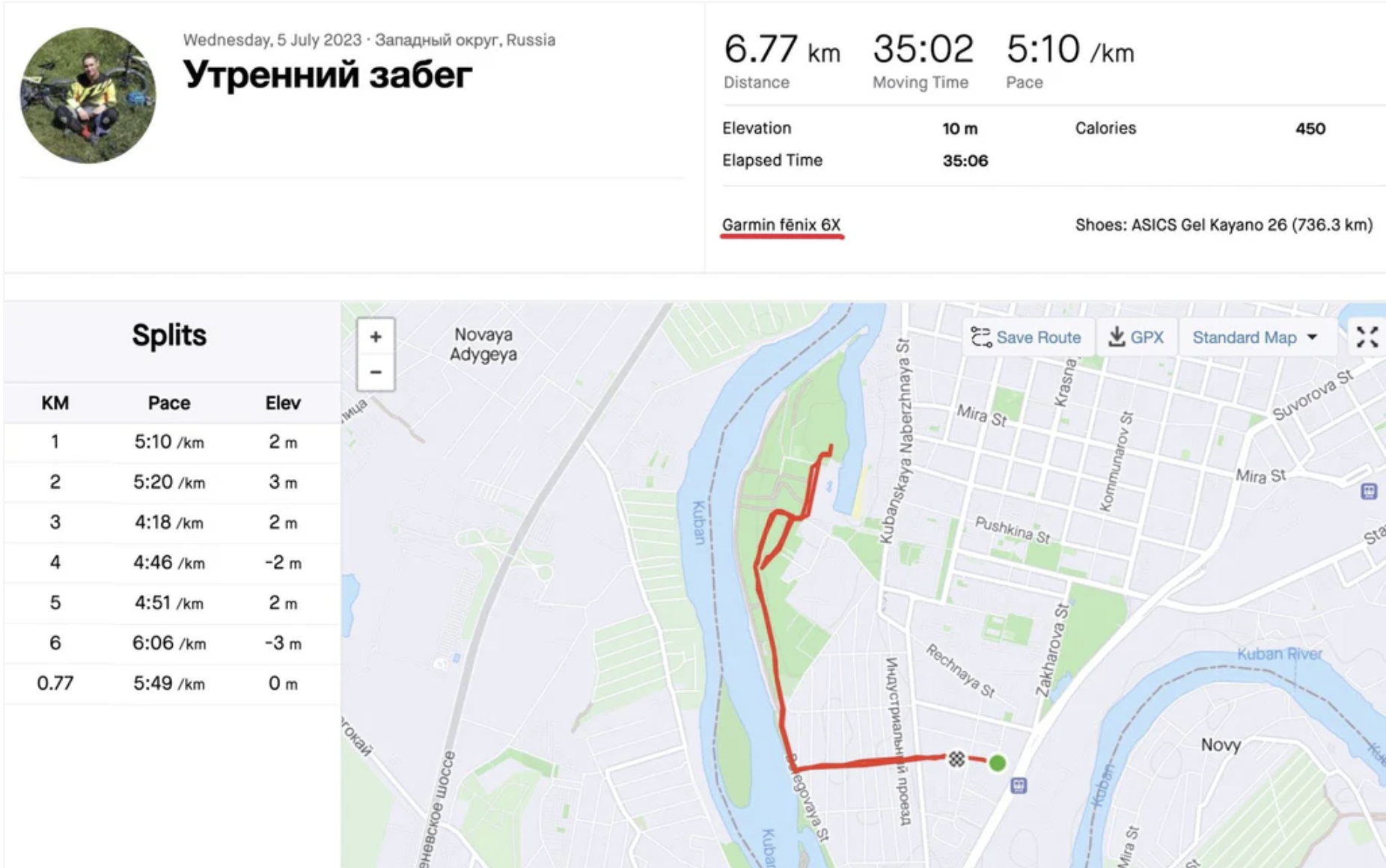

In 2023, a Russian naval commander was assassinated while jogging along a route that had been publicly documented through fitness tracking data tied to his real identity. The data included repeated GPS routes, timestamps, and photographs; enough information to establish location, routine, and positive identification. Whether the attack was intelligence-directed or criminal, the mechanism was the same: data voluntarily generated, publicly accessible, and quietly exploitable.

Similar issues have emerged around protective details for heads of state. Publicly shared workout data from security personnel has been used to reconstruct travel routes, private residences, and security patterns. These incidents have triggered internal investigations and policy reviews, not because the technology failed, but because its implications were underestimated.

Why This Matters Outside Intelligence Work

It is easy to dismiss these examples as irrelevant to ordinary people. Most readers are not intelligence officers, military commanders, or heads of state. But the underlying risk does not depend on status. It depends on exposure.

Smartwatch data does not need to be used for espionage to be harmful. The same datasets that support intelligence analysis can be used for stalking, harassment, financial exploitation, or targeted crime. Location data, routine behavior, and biometric indicators are valuable to anyone seeking leverage, not just state actors.

There is also a growing body of evidence showing that smartwatch sensors such as accelerometers can be analyzed to infer sensitive inputs, including passwords and payment information. Some devices have been found to carry malware that can access microphones, cameras, and linked accounts. These capabilities were once limited to advanced state actors. They are now increasingly accessible to criminal and commercial entities.

The Issue Isn’t Technology

None of this means smartwatches should be abandoned. They provide legitimate benefits for health, productivity, and situational awareness. The risk comes from misunderstanding what they are.

A smartwatch increases your attack surface. It adds another signal source, another metadata stream, and another system that can be exploited, misconfigured, or correlated. Wearing one does not make someone careless. Wearing one without understanding its implications does.

In environments where signal discipline matters, wearables are treated no differently than phones. They are controlled deliberately, removed when necessary, or excluded entirely. For civilians, the takeaway is not to mimic operational restrictions, but to recognize that any discussion of an electronic footprint that ignores wearables is incomplete.

Faraday Isolation as Signal Control

Faraday bags exist to address this exact problem. By creating a continuous conductive barrier around a device, they block both incoming and outgoing electromagnetic signals. When properly constructed with no gaps, weak seams, or compromised closures, a Faraday enclosure renders the device electrically silent.

This is why Faraday bags are regularly used in military, law enforcement, and intelligence environments where signal leakage can compromise operations.

Operational Signal Discipline From the Field (Sensitive but Unclassified)

Sometimes, it is beneficial for you to mask your electronic footprint while traveling. Today, technology is so abundant, that we have become almost dependent on our handheld devices that it is rare ever to see someone in an airport, or walking down the street without a smartphone in their hands. Even if you are not actively using your cell phone, it is broadcasting over the airwaves. All of the Apps you have loaded on your phone, run in the background. Third-party Apps have end-user agreements that are barely read by consumers and collect key data from you. Thieves and hackers can routinely intercept the signals from your electronic devices, and can open you up to having your system cloned or “hacked”, leaving your personal identification open to exploitation.

When choosing to eliminate or reduce your electronic footprint, there are very few ways to do it better than a Faraday Bag. Sure, just getting rid of your smartphone altogether is the best way, but that is not practical in today’s society. Turning your smartphone “off” or putting it into “airplane mode” does not stop it from emitting a signal. Most smartphones do not allow you to remove the battery these days, so using a Faraday Bag is the best solution.

A Faraday Bag is similar to the Faraday Cage. It is essentially a fine mesh enclosure that is made into a pouch, with either a leather or nylon exterior. The secret to this working is to create a constant, unbroken mesh around the electronic device. No seams, no voids. This mesh completely blocks incoming signals as well as any outgoing signals. The principle of the Faraday Bag is to leave you completely un-traceable, un-trackable, and most importantly un-hackable.

There are four tests you can do, to make sure your Faraday Bag is working the way it is designed. It must block Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, Radio Frequency, and Cellular connections. Before using my Faraday Bag, I would sync my smartphone with a Blue Tooth Speaker, and play music. If the music stops and the Bluetooth connection drops from the speaker when I secure my device in the Faraday Bag, then I know it is blocking Bluetooth signals effectively. You can check Wi-Fi effectiveness by watching your home Wi-Fi hub with your phone connected to the hub. Once you secure your device into the Faraday Bag, the device should drop from the network. You can also use your phone to call another phone, have the call active then secure your phone in the Faraday Bag. The call should drop, showing that cellular signals are also being blocked.

So, turning your device “off” and securing it into the Faraday Bag is the best way to travel with the device and have it immune to hacking and tracking. Choosing a reputable company to purchase a Faraday Bag from is fairly easy. Make sure the bag is tested and certified to block Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, RF, and Cellular signals.

Now, for the operational aspect of Faraday Bags. I was asked to provide a blurb of how we used these operationally. I will speak in general terms to not give away any Tactics, Techniques, or Procedures. First, a new sterile device was issued for every trip involving permissive, semi-permissive or non-permissive travel. No personal data was stored on the device, and vanilla SIM cards were used for the country of travel. Batteries and SIM cards were removed before travel when possible, and the devices were always stored in a Faraday Bag. Once on the ground, the device was activated only when necessary, and when the device was not used, it was stored in the Faraday Bag.

During the course of travel, it was not uncommon to use several different vanilla SIM cards. If internet (Wi-Fi) access was required, it was always done at a public internet café or public Wi-Fi connection hub. No personal information was ever used (Social Media, personal email, etc.) and the SIM card was replaced after each Wi-Fi session, with the device immediately secured into the Faraday Bag.

Granted, this is not feasible for most people. Limiting the number of Apps you have on your device, storing your device in a Faraday Bag while moving, and always using a REPUTABLE Virtual Private Network (VPN) when accessing Wi-Fi networks is something that can be worked into your daily schedule. We live in the Global Information Age. It is prudent for everyone to protect themselves. Purchasing a Faraday Bag and using common sense tactics, is a sure way to fortify your information security.

Civilian Signal Discipline

For civilians, the objective is not anonymity or counterintelligence tradecraft. It is conditional isolation.

Products such as the Mission Darkness Faraday Bags are designed to block common communication bands—cellular, GPS, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, RFID, and NFC—across a wide frequency range. Used correctly, they prevent passive signal emission during travel, storage, or transitional periods.

A Faraday bag does not replace encryption, account security, or responsible device use. It complements them by addressing a layer of exposure that software controls cannot mitigate: the simple fact that a device emits signals whenever it is electrically present.

External Storage, Air-Gapping, and Compartmentalization

Signal control loses value if sensitive data remains continuously accessible through networked systems.

What Air-Gapping Means

In computing terms, air-gapping refers to isolating data or systems from any network connection, whether wired or wireless. An air-gapped system cannot be accessed remotely because it is physically disconnected.

This concept originated in high-security environments but has practical civilian applications.

Air-Gapping in Everyday Use

For personal data, air-gapping often looks like this:

• Storing sensitive documents on encrypted external drives

• Keeping those drives disconnected except when intentionally accessed

• Avoiding cloud synchronization for critical files

• Separating everyday working data from identity-critical records

External solid-state drives are particularly suited for this role. When encrypted and stored offline, they dramatically reduce the attack surface. A compromised computer or account cannot expose data that is not stored on it or connected to it.

This principle applies as much to personal data as it does to secure facilities or classified networks.

The Negative Space

Most writing about privacy and personal security fails not because it is wrong, but because it stops too early.

The first and most consequential gap is how identity exposure is framed. Coverage tends to treat identity theft as an event, something that happens after a breach, a scan, or a hack. In practice, identity is rarely “taken” all at once. It is assembled slowly. Mail collected over months. Receipts pulled from trash. Location data inferred from routine device behavior. Signals correlated, not cracked. This cumulative process is well understood in intelligence and law enforcement contexts, yet largely absent from consumer-facing discussion.

A second gap is the separation of physical and digital risk. Articles often live entirely in one lane: cybersecurity or physical security. Paper disposal is discussed as old-fashioned. Signal emissions are treated as abstract or speculative. In reality, attackers do not care where the data comes from. Physical documents validate digital assumptions. Digital metadata fills in what paper cannot. Treating these as separate problems misunderstands how profiles are actually built.

There is also a persistent avoidance of passive collection. Much of the advice aimed at civilians assumes an active adversary, someone deliberately hacking a phone or skimming a card. Far less attention is paid to passive data capture: devices announcing themselves, networks logging associations, applications collecting metadata in the background. SIGINT works precisely because useful information exists even when no one is “doing” anything. That distinction rarely makes it into mainstream explanations.

Another missing piece is process versus product. Faraday bags, shredders, secure browsers, and external drives are frequently presented as solutions in isolation. What is usually left unsaid is that none of these tools matter without consistent behavior.

A P6 level shredder does nothing if documents sit uncollected in a mailbox. A Faraday bag is irrelevant if the phone lives outside it. Tools reduce exposure only when they are part of a routine.

There is also a lack of honesty about tradeoffs and limits. Most guidance either oversells protection or avoids stating what cannot be controlled. You cannot erase your digital footprint. You cannot exist in modern society without emitting signals.

What you can do is reduce your digital footprint, narrow your attack surface, and prevent easy aggregation of your personal data. That distinction, between protection and reduction, is rarely stated plainly.

Finally, institutional practices are often referenced without explanation. Military or intelligence methods are mentioned to lend weight, but the reader is left to infer whether and how those practices apply outside that context. The result is usually dismissal of the information. What is missing is the middle ground: explaining why those practices exist, what problem they solve, and how their underlying logic can be adapted without pretending civilians are operators.

This is the negative space most articles leave untouched. Not because the information is secret, but because it requires connecting systems instead of listing threats. It requires acknowledging that identity exposure is boring, incremental, and built from lazy habits.

Closing Assessment

Modern personal security is not about paranoia. It is about recognizing that identity exposure is cumulative and that small, consistent controls matter more than one-time actions.

Paper still leaks information. Devices emit signals. Data sits exposed. None of these is new. What has changed is the ease with which your data (physical and digital) can be collected and correlated.

Shredding and incineration deny physical reconstruction.

Faraday bag isolation controls when your devices talk to the world.

Air-gapping and compartmentalization limit information exhaust.

Individually, these measures are incomplete. Applied together, they form a robust approach to managing exposure in a world where information never stops moving.

Referenced Reporting

• Securing Your Information From Cyber Threats and RFID Hacking

• GoDark RFID Wallet: Protect Your Digital Life

• Best SSD External Hard Drive for Mac – SanDisk 1TB Portable SSD

• The Mission Darkness Faraday Bag Review: Why the NSA Trusts This Signal-Killing Tech

• Government Burn Bags and Document Disposal

*All analysis and conclusions are original to Gear Bunker Media.